Jim Hall's New Chaparral 2-C

Jim Hall (born July 23, 1935 in Abilene, Texas[1]) is a former racecar driver and constructor from the United States. He competed in Formula One from 1960 to 1963, participating in 12 World Championship Grands Prix and numerous non-Championship races.[2] His place in motorsport history came as the owner and driving force of Chaparral Cars of Midland, Texas. During the 1960s in the United States Road Racing Championship, and later in the CanAm, his Chaparral cars were the most innovative cars in racing. He was a very early adopter of aerodynamics applied to race cars and was leading proponent of that technology for an entire decade. He had a sabbatical in the early 1970s, racing in several NASCAR Grand American division pony car races. Hall came back to prominence in the Championship Auto Racing Teams series, including two wins in the Indianapolis 500 in 1978 and 1980; the latter with the first of the ground effect cars to be raced in the event. He would later turn to using off-the-shelf racecars to race in his Indycar team which was renamed Jim Hall Racing until 1996, when he retired from racing altogether. He now resides in Midland Texas, is active in the oil and gas business and motorsports racing legacies. The saga of Jim Hall and Chaparral Cars is documented at the Petroleum Museum in Midland, Texas. [1] His son, Jim Hall, Jr., resides in California and operates the Jim Hall Kart Racing School.

Jim Hall was known for innovation, and that innovation started to show itself in the Chaparral 2C, an upgraded version of the Chaparral 2A that included a hydraulic rear spoiler that the driver could raise in the turns and lower for less drag in the straightaways. The next evolution of Hall's racer, the Chaparral 2E made it's debut at the Can-Am race at Bridgehampton, New York in September 1966. This unique racer had a huge, high-mounted wing that, like the 2C's spoiler, was hydraulically operated to shift its angle depending on the track conditions. The Chaparral 2E and a later development versionn called the 2G had short racing careers, competing in 17 Can-Am races during 1966 through 1969. Although the car was unbeatable, it had reliability problems that resulted in many DNFs. The Chaparral 2Es and 2Gs actually only scored 2 Can-Am victories and 6 2nd place finishes.

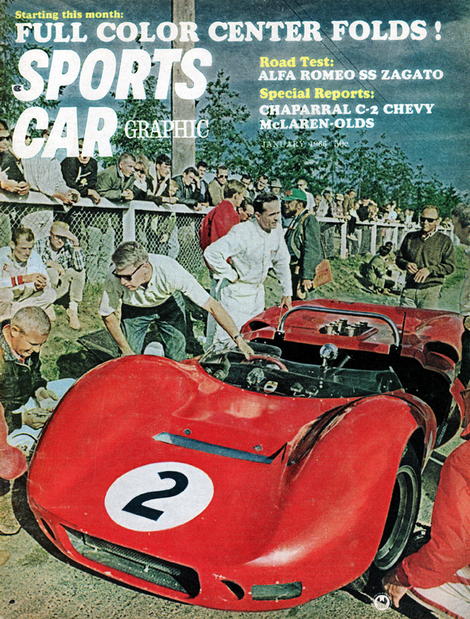

Jim Hall's New Chaparral 2-C

The 'old' Chaparrals were just about unbeatable...........so Jim Hall built a new, improved model!

text and photos: Pete Biro

WHEN YOU HAVE DESIGNED, BUILT AND ARE RACING THE MOST SUCCESSFUL SPORTS RACING CAR IN HISTORY - in 1965, through Riverside, nineteen races with fourteen Firsts and nine Seconds - there is only one thing you can do: Build a better car. And that is just what Jim Hall has done. He has built a better car: he has built the 2-C Chaparral.

Let's take a step back for a moment and we'll give you a short course in very important Chaparral nomenclature. Chaparral 1 was a front-engined tube-framed car, built by Troutman and Barnes, powered by Chevy, rather conventional, yet a winner in its time. The Chaparral 2 is a very different breed. Built by Jim Hall and his partners in Midland, Texas, the first model appeared at Riverside in 1963, and was clearly the quickest machine there, but was forced out with minor electrical fire while leading. It was the first, and still the only monocoque, plastic chassis sports/racer. With subsequent modifications that basic design (through 1964 and most of 1965) has, in 54 starts, finished in the money 38 times, and twice has given Jim the over-two-liter USRC Championship.

The easiest way to keep track of each individual car is by the name of the chief mechanics. The new 2-C is the responsibility of Carl Schmid. One of the plastic cars - there are three in current service, with two extra hulls - is handled by Franz Weis: his car is the lightest and the one Hap Sharp won at Riverside with. Wesley Sweet's car was Jim's choice for Laguna Seca, and was unfortunately crashed. Troy Roger's car the heaviest of the 2's, mainly because of repairs after Jim's Mosport accident. Wes' car will probably wind up weighing the same as Troy's. The plastic cars are actually designated 2-A's. The 2-B is the aluminum prototype used to make tests before building the 2-C. The new 2-C, shown here, had 5,000 test miles on it before its successful, wining debut at Kent, Washington. One additional 2-C is in the shop for a complete tear down every 1,500 miles.

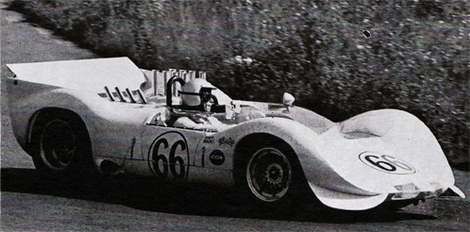

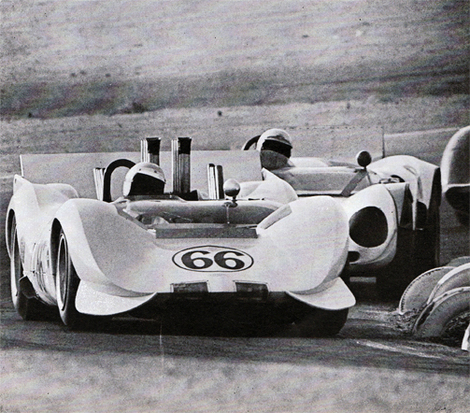

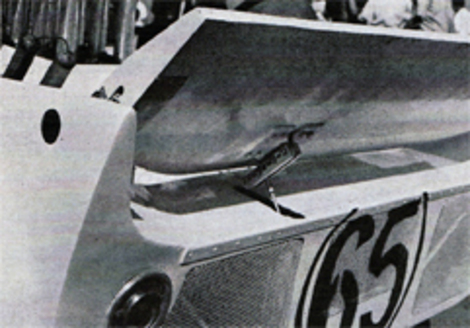

The low narrow silhouette of the new car with spoiler/brake in operation.

The low narrow silhouette of the new car with spoiler/brake in operation.

Other subtle aerodynamic changes have been made to the body's styling.

Other subtle aerodynamic changes have been made to the body's styling.

Construction of the 2-C began in May of 1965, and it was first track tested at Jim Hall's "Rattlesnake Raceway" on September 9. It is quite a bit smaller than its predecessors with a 90-inch wheelbase, and an overall body length 158 inches. Height at the cowl is 24 inches, with an additional five inches of windscreen, and the roll bar reaches 38 inches from the ground. Front tread width is 53.5 inches, rear tread is slightly narrower, at 52 inches. Front tires are Firestone 920x15, rears are 1200x15. Body width is 64 inches. "On the old cars, the big wide tires kept forcing us out to 70 inches" Jim said, adding: " Now we're right back where we started on our first car. We really had to squeeze to get everything back inside, at 64 inches. You'll notice there isn't room for front brake ducts on the newer car."

By "squeezing" Jim has reduced the frontal area of the new car from 14 to 13 square feet.

One of the greatest mysteries, a secret that all car builders hang on to, is the weight of their creations. Hall stated that his projected design weight was 1600 pounds on the grid with fuel and driver, ready to race. Jim says: "the car came out 40 pounds under design weight, so figuring a 175-pound driver, with 100 pounds of fuel, we should have a dry weight of 1285 pounds." In the past we've heard dry weight figures of 1170 pounds for one of the plastic cars. Jim said this car was 100 pounds lighter than the plastic car..........so we might be looking at a 1070-pound machine. Much weight is of course saved in the use of an aluminum engine, and without ant figures on the engine weight handy, it is realistic estimates.

The 2-C chassis structure is made of riveted and bonded aluminum alloys, with 0.032 sheet stock in the engine bay, 0.025 in less-loaded areas requiring the greatest strength. Jim describes his chassis as semi-monocoque, with no stringers, built with box sections. One of the major departures from the plastic cars is in the chassis: the seat area is not part of the structure.

"Design stiffness of the aluminum chassis is the same as plastic, but the ultimate stiffness of the plastic is about double." Jim smiled, adding: "But aluminum is lighter." Fuel is carried in rubber cells in the main chassis sections on this car, while the plastic cars carry fuel in the seats as well.

Hall prefers unvented brake discs, ducts cooling air into a "can". Considerable anti-dive is apparent in caster of the rear uprights and angle of coil/shocks.

Hall prefers unvented brake discs, ducts cooling air into a "can". Considerable anti-dive is apparent in caster of the rear uprights and angle of coil/shocks.

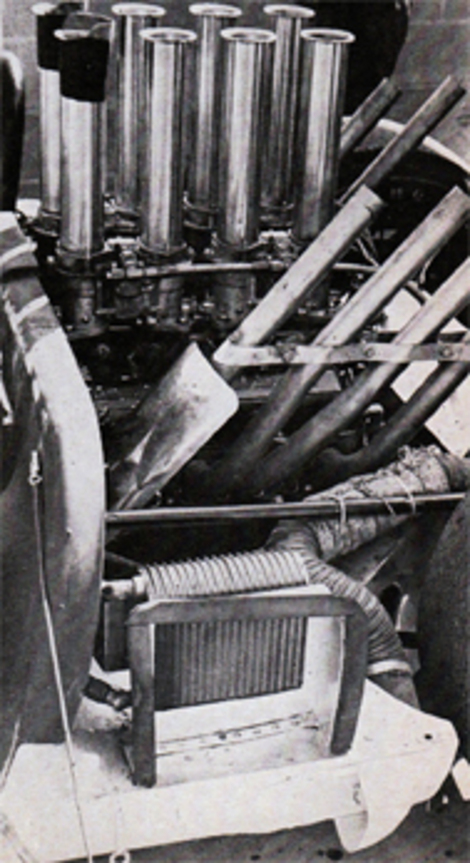

Air ducting to oil radiators located on both sides. Note small scopes on the forward intake ram tubes to correct, air-distribution as upset from cockpit turbulence.

Air ducting to oil radiators located on both sides. Note small scopes on the forward intake ram tubes to correct, air-distribution as upset from cockpit turbulence.

Although the big change is the obviously the switch to aluminum from plastic, that change which shook the opposition was in the aerodynamics. To get the slipperiest shaped car possible, air flow studies are constantly being made, with much attention to the proper ducting for components, as well as drivers. Every time one of his cars appeared there was a different duct, or flap, or a new snow-plow (first used at Mosport, to reduce front end lift). Well, the 2-C outdoes them all with a fantastic new combination spoiler, air-brake and psychological dampener. Jim told us that he got his first idea to use a spoiler on his cars after seeing one on a Ferrari. Phil Hill told us the very first use of a spoiler on a Ferrari was in '62 at Nurburgring, when he set the lap record in the 2.6 four-cammer. Phil said: "The addition of the spoiler was the only thing that made the rear-engined Ferrari handle." Used on Richie Ginther's GTO the spoiler gained the nickname of the "Ginther Lip." Now, withJim Hall's super-spoiler, the rest of the fraternity should be calling it "Hall's Harrasser." After Jim rolled the 2-C into public view at Kent and proceeded to destory the track records, just about every crew there was seen hanging sheet metal on the tail ends of their cars. And by Luguna Seca nearly every car was so equipped. Jim says a spoiler really stabilizes his car. "It's like the feathers on an arrow. Take the feathers away and watch what happens to the arrow." Jim's adjustable spoiler has the advantage of being removable, aerodynamically, to reduce frontal area at times when the added stability is not needed. He has three basic trim positions, one for corners, one for the straight and one for braking. Shaped like an airfoil, it is pivoted on its center of pressure, and can pick its own best weather-vaning position, when let free. Hall was surprised to see everyone else take so long to realize the need for spoilers.

It would be practically impossible for anyone with a manual transmission in their racers to use an adjustable spoiler like Jim's, as he operates it via mechanical linkage with his left foot. This foot is needed for clutch operating by his competition. Pushing down on the stabilizer pedal brings it up, while other positions can be attained by backing off the pedal. A slightly different set-up was fitted to the car that Sharp ran at Riverside, utilizing hydraulics. The hydraulic reservoir was mounted alongside the dual brake master cylinders, and looked like a mounting arrangement from one of the old manual-transmission cars. Knowing Jim, this was probably done to keep 'em guessing, as he is so inclined to do. In a light moment Jim told a group of curiosity seekers that they had the linkage wrong on Hap's car, and the first time he went down to the number five shutoff marker, the spoiler locked up, pushing him right out of the cockpit.

Hall checks spoiler with makeshift mounting points. Note that actuating rod is set in the extreme rear position to minimize the total stress.

Hall checks spoiler with makeshift mounting points. Note that actuating rod is set in the extreme rear position to minimize the total stress.

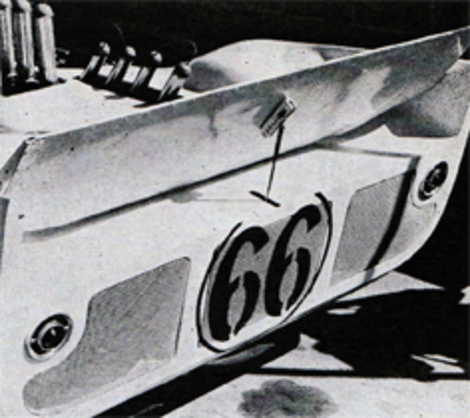

A fatter Kamm-edged spoiler was used on Sharp's car, with entirely different geometry applied to actuating linkage and its pickup mounting.

A fatter Kamm-edged spoiler was used on Sharp's car, with entirely different geometry applied to actuating linkage and its pickup mounting.

Airflow through the radiator enters at a high pressure area under the low ground hugging snout, and exits at the low pressure area on the hood ahead of the windscreen. A side-mounted air duct on the left, behind the cockpit, feeds air to the engine oil cooler. Front brake air is brought in alongside the radiator air inlet. Rear brake air enters just ahead of the rear wheel wells. Sheet metal ducting for the radiators also carry Marchal iodine lamps.

Anyone that has had the opportunity to stand out on a corner to watch the Chaparrals pour all of their power right to the asphalt has to realize that Jim is way ahead of the field when it comes to road holding. Suspension components at the front combine both tubular and sheet metal wishbones. The sheet metal units are used where greater load requirements are needed. Adjustable telescopic shocks are fitted, wrapped with coil springers. An anti-sway bar is fitted, mounted in Teflon bearings, running across the foot-box section forward to links with the upper sheet metal wishbone. Front end geometry incorporates anti-dive. For stopping power Kelsey-Hayes made Girling CR calipers are fitted to the rear of the front mounted outboard discs. Apparently Jim has seen no reason to go to the vented discs that others are using. We suspect that an aircraft-type high-boiling-point fluid must be used on the Chaparrals; they seem to be running with very little brake trouble, even though they use them more severely than cars with manual, shift-down able transmissions. Brake lines throughout are aircraft standard steel braided. Very light rack and pinion steering, with two turns lock-to-lock, is fitted.

More permanent mounting is faired into the rear fender. Size of the actuating rod would indicate there was a great deal of pressure.

More permanent mounting is faired into the rear fender. Size of the actuating rod would indicate there was a great deal of pressure.

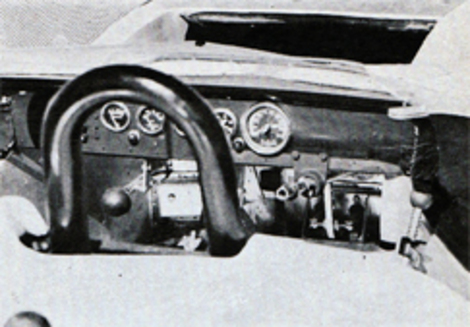

Black pedal directly below tachometer is presumed to actuate the rear fin, but there is some question about the way it operates in actual use.

Black pedal directly below tachometer is presumed to actuate the rear fin, but there is some question about the way it operates in actual use.

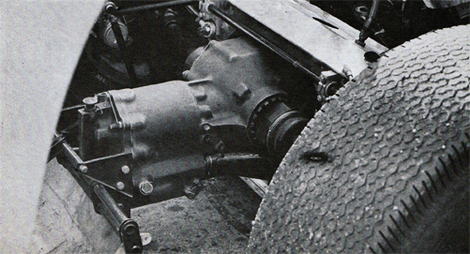

Another Chaparral mystery - always worthy of a picture - is the gearbox. Aside from the obvious quick-change configuration at the rear, outside clues as to its design are just about nil. The absence of a cooler gives rise to further speculation. Shift linkage is below the right U-joint.

Another Chaparral mystery - always worthy of a picture - is the gearbox. Aside from the obvious quick-change configuration at the rear, outside clues as to its design are just about nil. The absence of a cooler gives rise to further speculation. Shift linkage is below the right U-joint.

Jim has designed a rear suspension that has anti-squat and anti-lift. This means when he gets on the go pedal the car doesn't squat, and when applying the brakes, his car in conjunction with the front anti-dive, remains dead level. The cast rear hub carrier is located 20-degrees off vertical via a tubular reversed lower wishbone, a single upper side-link and a pair of trailing links. As at the front shocks are coil wrapped. The anti-sway bar mounts at the rear of the chassis bulkhead, over the transaxle, and joins the outer end of the lower wishbones via links. The forward end of the trailing links attach to the chassis via a large tube structure that forms the roll bar support. Rear brake calipers are BR's with the discs fully ducted. The rear bodywork and the spoiler linkage attaches to the back of the automatic transaxle housing.

As far as the engine is concerned, Jim has thrown out all the "bag of snakes" exhaust theories, using individual tuned-length stacks. He tends to run extremely long intake rams, tuned for torque. Weber down-draft carburetors, of both 48 mm and 58 mm size, have been used, with more power claimed for the 58's, but with less range. Jim says he's still using only 327-inches, with a bore of four inches and stroke of 3.5 inches. Compression ratio is relatively mild 10.5 to 1. Power is said to be 450 SAE horsepower. And the engine redline is at 6800 rpm.

What's inside the canvas-covered automatic transaxle still remains a mystery, and to quote Jim on his feelings: "If you have something that works, you had better keep it quiet, or by the next race everybody will have it". With the competition as fierce as it is we don't blame him for this philosophy. One of Jim's mechanic's favorite games is catching squirrels who have crawled under the car to sneak a look. And there are plenty being caught.

Nuts and bolts-wise that about covers the new "2-C" Chaparral. Probably the greatest speed secret that the Chaparral cars have is the most obvious ingredient of their operation - the people of Chaparral cars. This is a very serious dedicated group of racers. Their mechanics do not come from racing background. The German crewmen are factory trained VW mechanics. Every one is very thorough, all have a terrific amount of respect for one another, as well as their bosses. At Riverside, when an all-night preparation session was needed, Jim, Hap, and Sandy Hall, Jim's wife, stayed with the crew 'til the wee hours. Jim supervised the operation, while Hap and Sandy played a mean game of Gin, as well as adding moral support to the cause. Sandy is always ready with the coffee. She also keeps records on every lap time turned by a Chaparral, or the opposition. On lap time charts Sandy keeps, she notes changes made in the cars from a quarter-turn on the brake balance bar adjustment to a one-eighth-inch change in spoiler linkage.

You just can't beat people like this!

Chaparral 2 starts up.

Chaparral 2E on the road.

Chaparral 2E warms up.

Chaparral Cars was a United States automotive company which built prototype race cars from the 1960s through the early 1980s. Chaparral was founded by Jim Hall, a Texas oil magnate with an impressive combination of skills in engineering and race car driving. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Chaparral's distinctive race cars experienced strong success in both American and European racing circuits. Despite winning the Indy 500 in 1980, the Chaparrals left motor racing in 1982. Chaparral cars also featured in the SCCA/CASC CanAm series and in the European FIA Group 7. It is also said in popular culture that the Chaparral race cars were barred from events because of them being too effective and fast, especially the 2J. Chaparral was the first to introduce effectively designed air dams and spoilers ranging from the tabs attached to the earliest 2 model to the driver-controlled high wing 'flipper' on the astoundingly different looking 2E, all the way through to Hall's most idealistically inspired creation, the 2J, the car that would forever be known as the 'vacuum cleaner'. The use by Jim Hall of a semi-automatic transmission in the Chaparral created flexibility in the use of adjustable aerodynamic devices. The development of the Chaparral chronicles the key changes in race cars in the '60s and '70s in both aerodynamics and tires. Jim Hall's training as an engineer taught him to approach problems in a methodical manner and his access to the engineering team at Chevrolet as well as at Firestone changed aerodynamics and race car handling from an art to empirical science. The embryonic data acquisition systems created by the GM R&D group aided these efforts. An interview with Jim Hall by Paul Haney [1] illustrates many of these developments.

The Chaparral 2-Series was designed and built to compete in the United States Road Racing Championship and other sports car races of the time, particularly the West Cost Series that were held each fall. Following the lead of innovators like Bill Sadler from Canada and Colin Chapman who introduced rear engined cars to Grand Prix cars in Europe (where Jim Hall had raced in Formula 1), its basic design concept was a rear engined car. First raced in 1963, it was developed into the dominant car in the series in 1964 and 1965. Designed for the 200 mile races of the sports car series, it was almost impossible to beat. It proved that in 1965 by winning the 12 Hours of Sebring on one of the roughest tracks in North America. As the car was being developed, Jim Hall took the opportunity to implement his theories on aerodynamic force and rear wheel weight bias. In addition, the Chaparral 2-Series featured the innovative use of fiberglass as a structural element. Hall also developed 2-Series cars with conventional aluminum chassis. It is very difficult to identify all iterations of the car as new ideas were being tested continually. There are three generally accepted variants: â–ª The 2A is the car as originally raced, featuring a very conventional sharp edge to cut through the air. It also featured a square tail with a concave tail reminiscent of the theories of Dr Kamm. Almost immediately an issue with the front end being very light at speed with a consequent impact on steering accuracy and driver confidence. The first aerodynamic appendages began to appear on the 2A. â–ª The 2B was the name applied to the cars with the full package of “aero tweaksâ€, chin spoilers, fender slots and rear spoiler. â–ª The 2C was the name applied to the car with the first in-car adjustable rear wing which was designed to be flat on the straight and tipped up to add rear downforce under braking and in corners. This was a direct benefit of the automatic transmission which kept the left foot free to operate the wing mechanism. The 2C was based on a Chevrolet designed aluminum chassis and was a much smaller car in every dimension than the 2A. Without the natural non-resonant damping of the fiberglass chassis, Jim Hall nicknamed it the EBJ, “Eye Ball Jiggler.†Coincidental with the development of aerodynamics was Hall's development of race tires

Models by the score are available of this car.

Models by the score are available of this car.

Posted 11/11/08 @ 02:48 PM | Tags: Jim Hall, Chaparral 2c, Sports Car Graphic magazine, Sports Car Graphic magazine January 1966, Richie Ginther's GTO, Girling brakes, Weber carburetors, Bill Sadler, Colin Chapman, Chaparral